French Revolution Fashion French Revolution Fashion Poor

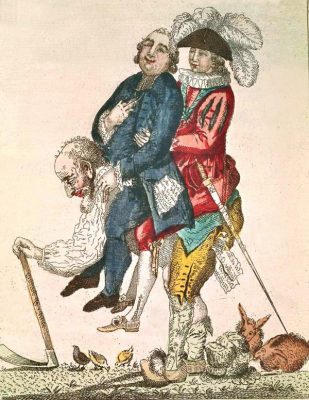

Before the revolution, French society was divided into three orders or Estates of the Realm – the First Estate (clergy), Second Estate (dignity) and Tertiary Manor (commoners). With around 27 million people or 98 per cent of the population, the Third Manor was by far the largest of the three – but it was politically invisible and wielded little or no influence on the government.

Multifariousness

As might exist expected in such a sizeable group, the Third Estate boasted considerable diverseness. There were many unlike classes and levels of wealth; unlike professions and ideas; rural, provincial and urban residents alike.

Members of the Third Manor ranged from lowly beggars and struggling peasants to urban artisans and labourers; from the shopkeepers and commercial middle classes to the nation'south wealthiest merchants and capitalists.

Despite the Third Estate's enormous size and economic importance, information technology played virtually no part in the government or decision-making of the Ancien Authorities. The frustrations, grievances and sufferings of the Third Estate became pivotal causes of the French Revolution.

The peasantry

Peasants inhabited the lesser tier of the Third Estate's social hierarchy. Comprising between 82 and 88 per cent of the population, peasant-farmers were the nation'southward poorest social class.

While levels of wealth and income varied, it is reasonable to suggest that near French peasants were poor. A very small percentage of peasants owned state in their own right and were able to live independently equally yeoman farmers. The vast majority, however, were either feudal tenants, métayers (tenant sharecroppers who worked someone else's land) or journaliers (day labourers who sought work where they could find information technology).

Whatever their personal situation, all peasants were heavily taxed past the country. If they were feudal tenants, peasants were also required to pay ante to their local seigneur or lord. If they belonged to a parish, every bit most did, they were expected to pay an annual tithe to the church.

These obligations were seldom relaxed, fifty-fifty during difficult periods such equally poor harvests, when many peasants were pushed to the brink of starvation.

Urban commoners

Other members of the Third Estate lived and worked in French republic'southward towns and cities. While the 18th century was a period of industrial and urban growth in French republic, most cities remained insufficiently small. There were merely nine French cities with a population exceeding 50,000 people. Paris, with around 650,000, was by far the largest.

Most commoners in the towns and cities made their living as merchants, skilled artisans or unskilled workers. Artisans worked in industries similar textiles and wear manufacture, upholstery and piece of furniture, clock making, locksmithing, leather goods, wagon making and repair, carpentry and masonry.

A few artisans operated their ain business concern but well-nigh worked for large firms or employers. Earlier doing business or gaining employment, an artisan had to belong to the guild that managed and regulated his particular industry.

Unskilled labourers worked as servants, cleaners, hauliers, h2o carriers, washerwomen, hawkers – in short, annihilation that did not require preparation or membership of a guild. Many Parisians, perhaps every bit many equally eighty,000 people, had no job at all: they survived by begging, scavenging, petty crime or prostitution.

The difficult 1780s

The lives of urban workers became increasingly difficult in the 1780s. Parisian workers toiled for meagre wages: between 30 and 60 sous a twenty-four hour period for skilled labourers and 15-20 sous a day for the unskilled. Wages rose by around 20 per cent in the 25 years earlier 1789, however prices and rents increased past 60 per cent in the same flow.

The poor harvests of 1788-89 pushed Parisian workers to the brink past driving up breadstuff prices. In early on 1789, the toll of a four-pound loaf of bread in Paris increased from nine sous to xiv.5 sous, nearly a full day's pay for most unskilled labourers.

Low pay and high food prices were compounded by the miserable living conditions in Paris. Accommodation in the capital was so scarce that workers and their families crammed into shared attics and dirty tenements, most rented from unscrupulous landlords.

With rents running at several sous a day, most workers economised by sharing adaptation. Many rooms housed between half-dozen and x people, though 12 to fifteen per room was not unknown. Conditions in these tenements were cramped, unhygienic and uncomfortable. In that location was no heating, plumbing or common ablutions. The toilet facilities were usually an outside cesspit or open sewer while water was fetched by hand from communal wells.

The affluent bourgeoisie

Non all members of the Third Estate were impoverished. At the apex of the Third Estate'due south social bureaucracy was the bourgeoisie or backer middle classes.

The suburbia were business owners and professionals with plenty wealth to live comfortably. Equally with the peasantry, there was besides diversity inside their ranks.

The so-called petit bourgeoisie ('piffling' or 'small-scalebourgeoisie') were pocket-sized traders, landlords, shopkeepers and managers. The haute bourgeoisie ('high suburbia') were wealthy merchants and traders, colonial landholders, industrialists, bankers and financiers, tax farmers and trained professionals, such as doctors and lawyers.

The bourgeoisie flourished during the 1700s, due in office to France'southward economic growth, modernisation, increased production, imperial expansion and foreign trade. The haute suburbia rose from the center classes to become independently wealthy, well-educated and aggressive.

Political aspirations

Every bit their wealth increased so did their want for social status and political representation. Many bourgeoisie craved entry into the Second Estate. They had money to acquire the costumes and grand residences of the noble classes but lacked their titles, privileges and prestige.

A system of venality evolved that allowed the wealthiest of thebourgeoisie to buy their style into the nobility, though past the 1780s this was becoming more than hard and frightfully expensive.

The thwarted social and political ambitions of the bourgeoisie led to considerable frustration. The haute bourgeoisie had become the economic masters of the nation, nonetheless government and policy remained the domain of the royalty and their noble favourites.

The revolutionary bourgeoisie

Many educated bourgeoisie establish solace in Enlightenment tracts, which challenged the foundation of monarchical power and argued that authorities should be representative, accountable and based on popular sovereignty.

When Emmanuel Sieyes published What is the Third Estate? in January 1789, it struck a chord with the self-important bourgeoisie, many of whom believed themselves entitled to a mitt in government.

What is the Tertiary Estate? was not the only expression of this idea; there was a flood of similar pamphlets and essays around the nation in early 1789. When these documents spoke of the 3rd Estate, yet, they referred chiefly to the suburbia – non to France's 22 million rural peasants, landless labourers or urban workers.

When the suburbia dreamed of representative government, it was a government that represented the propertied classes only. The peasants and urban workers were politically invisible to the bourgeoisie – just as the bourgeoisie was itself politically invisible to theAncien Régime.

A historian's view:

"The social construction on the European continent withal bore an aristocratic imprint, the legacy of an era when, considering country was near the sole source of wealth, those who owned information technology assumed all rights over those who worked information technology… Almost the whole population was lumped into a '3rd social club', called in France the Third Estate. Aristocratic prerogatives condemned this social club to remain eternally in its original state of inferiority. [But] throughout … France, this ordering of club was challenged past a long-term modify which increased the importance of mobile wealth and the bourgeoisie, and highlighted the leading role of productive labour, inventive intelligence and scientific knowledge."

Georges Lefebvre

1. The Tertiary Estate contained around 27 one thousand thousand people or 98 per cent of the nation. This included every French person who did non have a noble title or was not ordained in the church.

2. The rural peasantry made upwards the largest portion of the Third Estate. Most peasants worked the land as feudal tenants or sharecroppers and were required to pay a range of taxes, tithes and feudal ante.

3. A much smaller section of the 3rd Manor were skilled and unskilled urban workers, living in cities like Paris. They were poorly paid, lived in hard atmospheric condition and were pressured by rising food prices.

4. At the summit of the Third Manor was the bourgeoisie: successful business owners who ranged from the comfortable middle class to extremely wealthy merchants and landowners.

five. Regardless of their property and wealth, members of the Third Estate were bailiwick to caitiff taxation and were politically disregarded past the Ancien Régime. This exclusion contributed to rising revolutionary sentiment in the tardily 1780s.

Citation information

Title: "The Third Manor"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Blastoff History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/third-estate/

Engagement published: September 23, 2020

Date accessed: February nineteen, 2022

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, delight refer to our Terms of Use.

0 Response to "French Revolution Fashion French Revolution Fashion Poor"

Post a Comment